A LITTLE PREAMBLE

Up to the beginning of the twentieth century the accepted method of joining together ship hull plating was through the use of rivet type mechanical fasteners. In the beginning these rivets had a head and heal that stood proud of the hulls exterior and interior. The flush fitting rivets -- where the V-shaped head of the rivet compressed into the chamfered hole of the plate -- came into vogue, in some applications, during the later nineteenth century.

This discussion will be focused on the three most common rivet types we would see on a ship or submarine built in the, 'age of sail'.

Before the almost universal practice of welding had replaced the rivet as the principle means of affixing metal hull plates together, rivets were the preferred method of bonding metal-to-metal. And, as you would guess, there were many different head styles of rivet, as well as patterns to which the rivets were laid down.

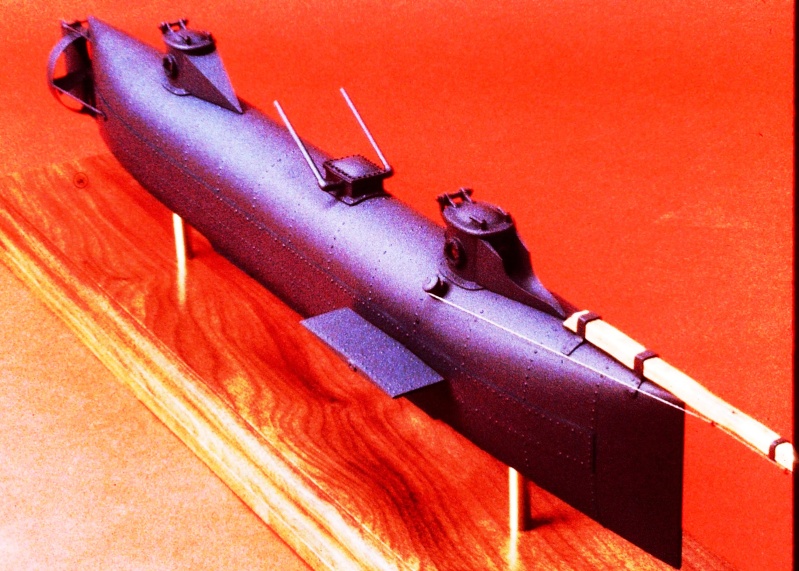

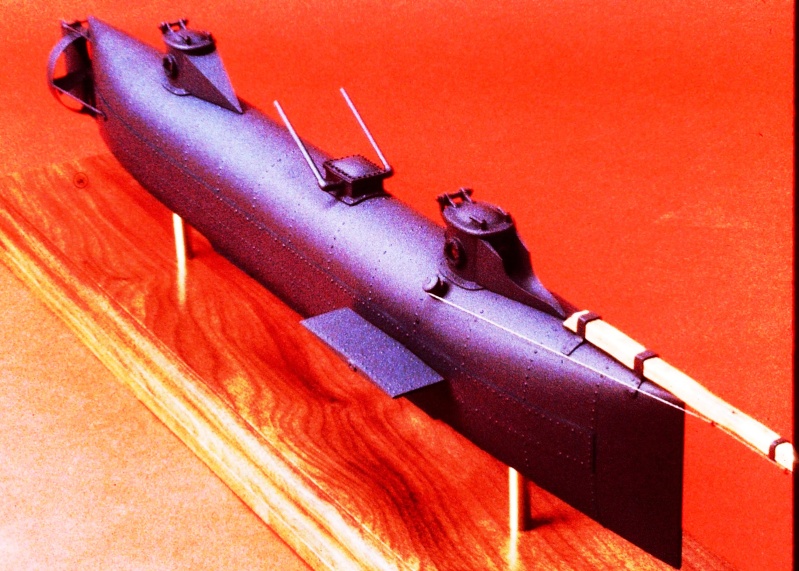

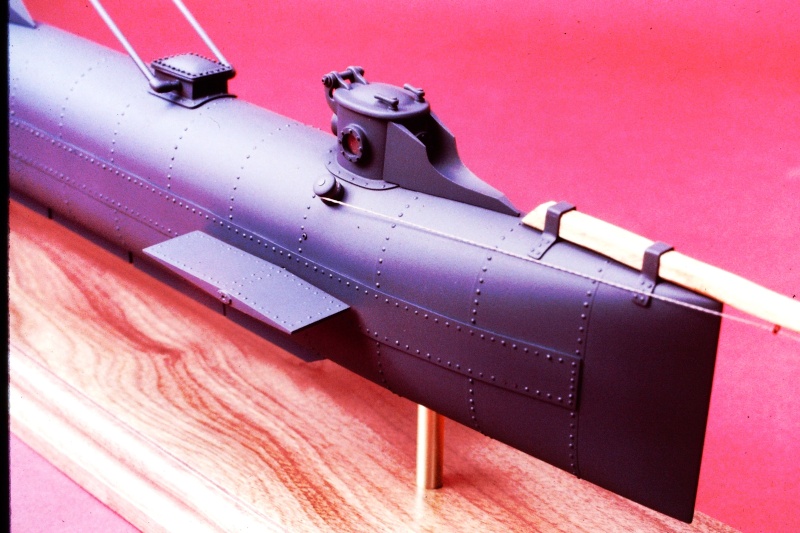

Presented here are model representations of the round, flat, and counter-sunk type rivets. The subjects are a r/c 1/16 USS ALLIGATOR; an r/c 1/12 HUNLEY Confederate privateer; and a smaller static display 1/24 HUNLEY.

Before launching into the discussion proper, I want to inform the reader that both HUNLEY models used as examples here were commissioned and built long before the HUNLEY revelations -- after examination of the salvaged original submarine off the coast of Charleston.

it's interesting to note that the Confederate And Union submarines of the Civil War were both constructed of metal butt-joined (carvel plating) metal plate held tightly together by counter-sunk rivet s whose round heads were flat and flush with the outer surface of the hull. A streamlining measure only recently appreciated my marine vessel Conservators and historians.

(It was not until the salvage and examination of the actual HUNLEY did we realize the error all the illustrators and model-builders made previous to that revelation: we all assumed round-head rivets sticking high and proud off the submarines hull).

The two HUNLEY models are presented here to demonstrate two different technique for representing round-head type rivets over lap-joined and radial clinker hull plating. These models are poor representations of the actual HUNLEY submarine, but have utility here as very good rivet application training-aids.

THE SUBJECTS CHOSEN TO DEMONSTRATE MY RIVETING TECHNIQUES

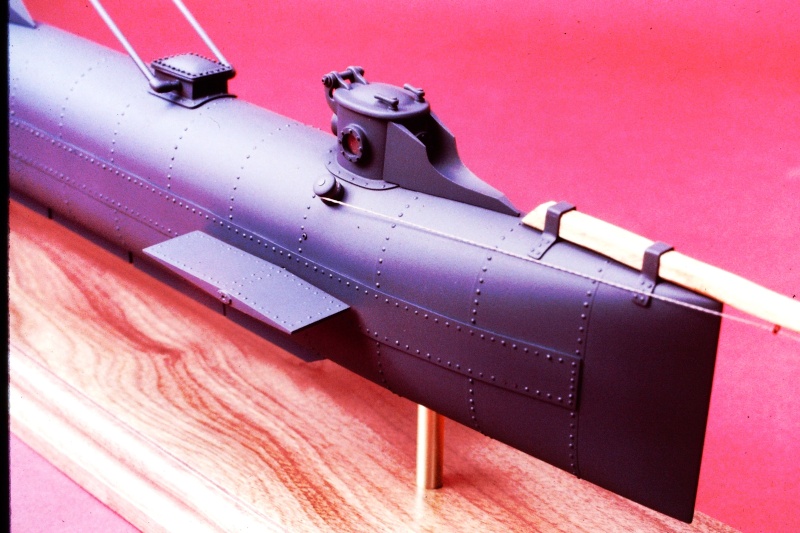

This 1/16 scale effects miniature represents the USS ALLIGATOR. America's first commissioned submarine. It commissioned for and appeared on the Discovery Science Channel episode, The Hunt For The Alligator. A fully capable r/c model submarine, this effects miniature featured screw-type propeller propulsion; a gas type ballast sub-system; deployable anchor; practical diver and conning hatches; and practical suspension floats -- used to stabilize the boat about the pitch axis and suspend the submarine at specific depth from the surface through deployment and recovery of the float lines.

(An interesting aside: While filming the TV show it was found that the deployed stabilization buoys raised the vehicles center of buoyancy so high above its center of gravity that even at a significant advance through the water, the static stability of the boat about the pitch axis was so high as to counter the dynamic forces that would have otherwise (with a closely coupled c.b. and c.g.) made the boat unstable about the pitch axis. The ALLIGATOR had no horizontal control surfaces! No active means of controlling the boats pitch angle. Yet, it was found during our use of the effects miniatures during production, that with the buoys deployed (as seen in this production shot) that I could control the boat easily by slight changes in the amount of ballast water aboard. The deployed buoys keep the submarine on a near zero pitch angle -- deep control was effected by ballast water taken on/pumped out alone!).

The 1/12 HUNLEY: Though I was not involved in the hull construction of this model, I was dragooned into the project as the initial builders became preoccupied with other work. I took on this model after receiving the basic hull, with little else. Because this model is based on the W.A. Alexander sketches -- a document so highly referenced over the decades as to have become almost canon until recent times -- this model IS NOT a proper representation of what we now know the HUNLEY to be.

If only we had followed the Chapman miniature painting and pencil studies -- which were first-person depictions of the vessel -- we would have been very close to what the Conservators recently found out.

The written and illustrated history bit me on the ass on this one.

However, I did complete the model and r/c'ed it for the customer. And it worked surprisingly well underwater. As long as the speed was kept below a critical limit, the single set of bow planes was enough to effect good depth control. But, above the critical speed the boat would either pitch up or down violently. And that's why the real boat worked so well: being man powered, it could never attain a speed where the static stability of the boat was defeated by hydrodynamic forces created as a consequence of speed, i.e. the boat worked because it was slow. It was man-powered.

This wooden and cast resin 1/24 static display model was commissioned by a collector. And, like the above r/c HUNLEY was built based on the rather inaccurate drawings based on the sketches of W.A. Alexander.

NOW ... THE RIVETS DISCUSSION

COUNTER-SUNK (FLUSH) RIVETS AS ENGRAVED CIRCLES The little known (historian's have been so negligent in regards to this incredible submarine) or appreciated Union ALLIGATOR, a contemporary of the Confederate HUNLEY, likely was built with the same type materials and fasteners as her southern sister. I was commissioned to build model, an effects miniature, representing the arrangement of the ALLAGATOR shortly before its loss while being towed around Cape Hatteras.

A fortunate circumstance: at the time the salvaged HUNLEY was giving up her secrets, I began design and physical work on the miniature -- I endeavored to detail the ALLIGATOR by representing the same type plating joins, fasteners, and manufacturing techniques seen on the HUNLEY.

That meant that the hull plating rivets would be represented as circles, each defining the perimeter of the rivet head as it sat in its chamfered hole in the plate. The models hull would have to be engraved with hundreds of little circles. On the other hand, those structures mounted onto the hull would be outfitted with simulated flat type rivets, that sat proud upon the items mounting flange -- those rivets represented by little punched out discs of .010" polystyrene sheet.

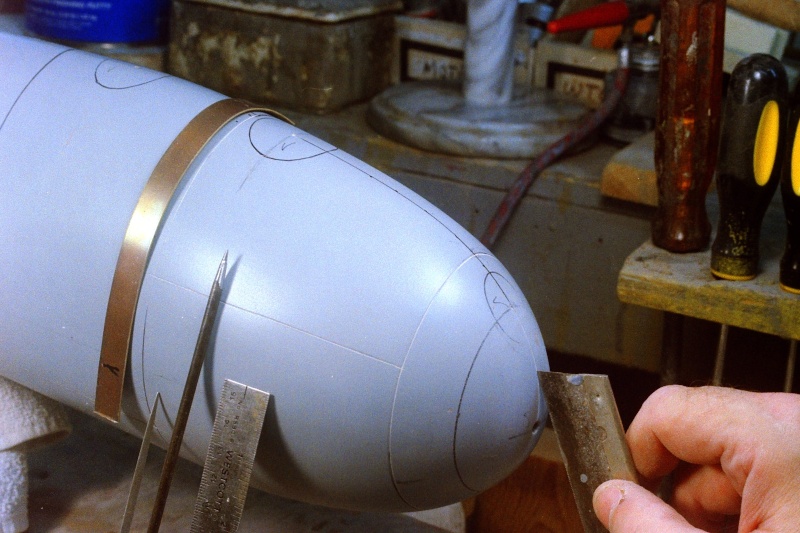

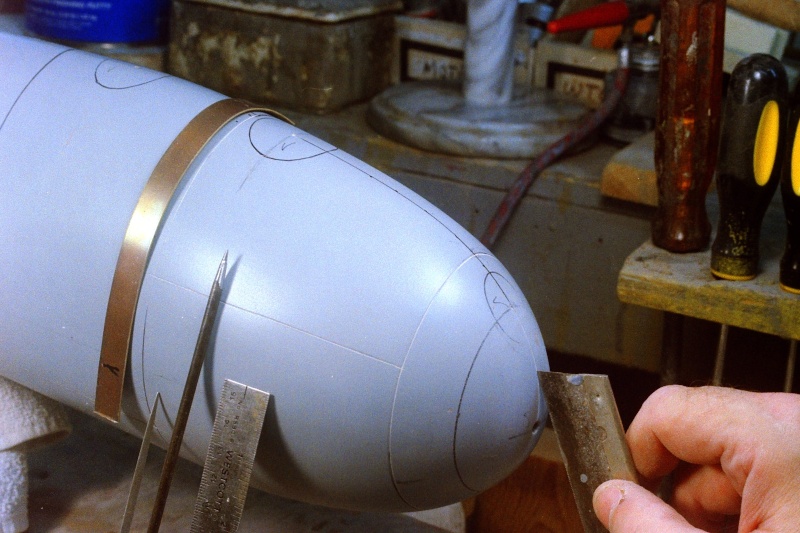

The hull proper, a GRP structure with a heavy gel-coat serving as the outer substrate, was first marked off with pencil to denote the butt plate joins.

The productions main art-director and ALLIGATOR expert, Jim Christly, informed me that the hull was likely made from rolled sheet of iron plate that came from the mill in four-foot wide sections. Scaling that to the model gave me the longitudinal distance between engraved radial lines (used to represent the butt-joints between plates).

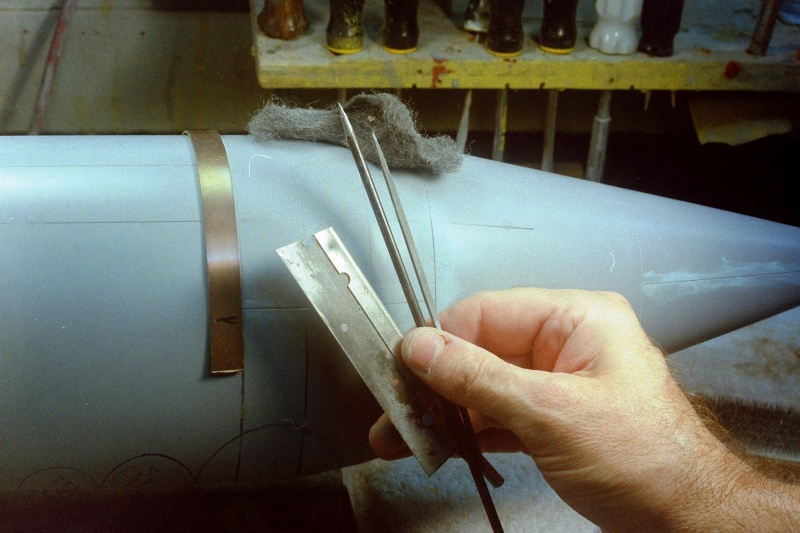

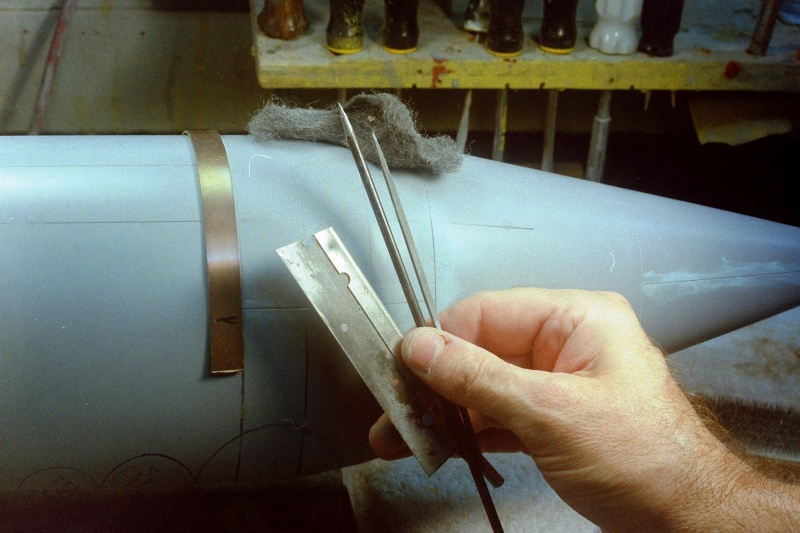

Scribing scratch-awl and razor saw were used to cut in the radial and longitudinal engraved lines -- I had planned for this when laying up the hull GRP parts -- having taken care to provide a very heavily filled gel-coat before laying down the glass laminates. It's easy to scribe soft gel-coat. It's a complete son-of-bitch to engrave across strands of glass! A lesson learned early in my model-building career.

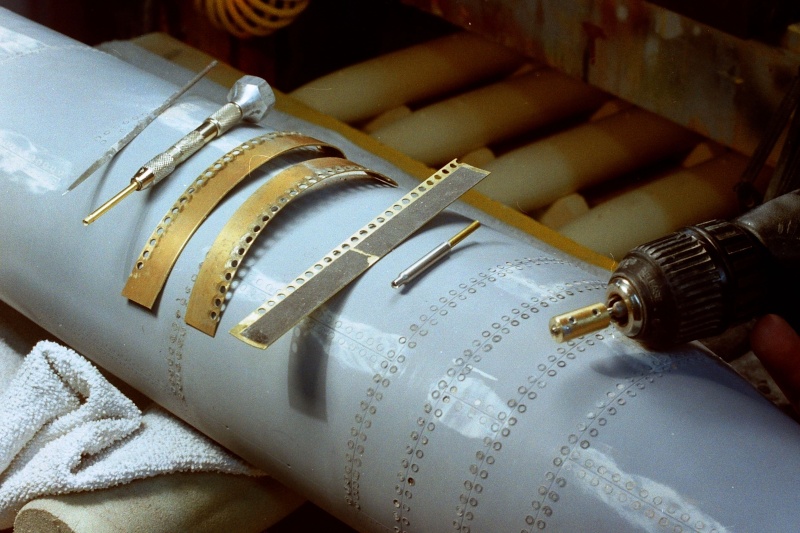

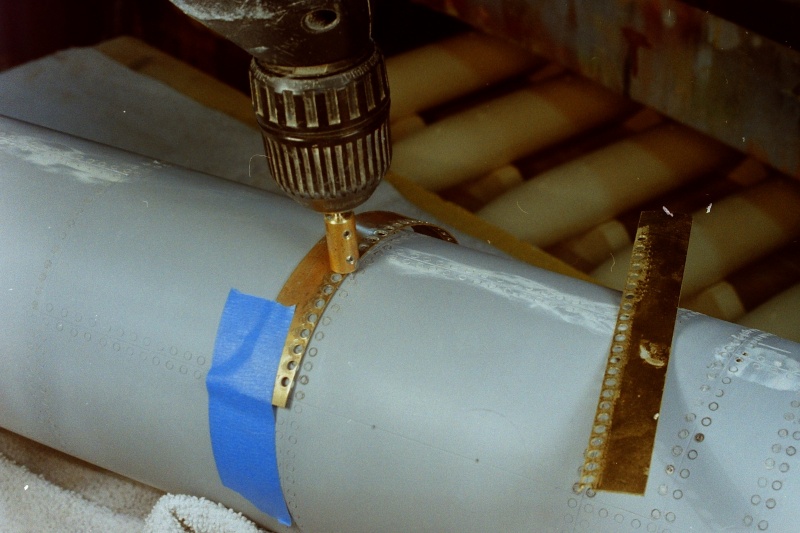

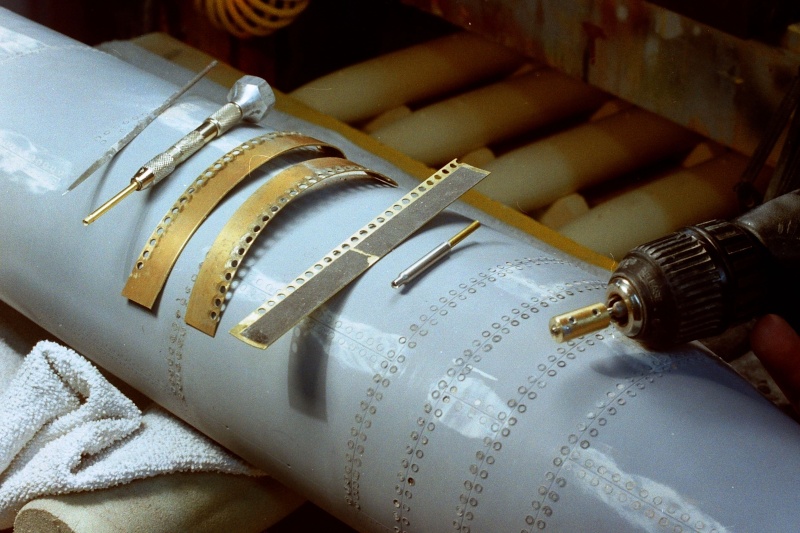

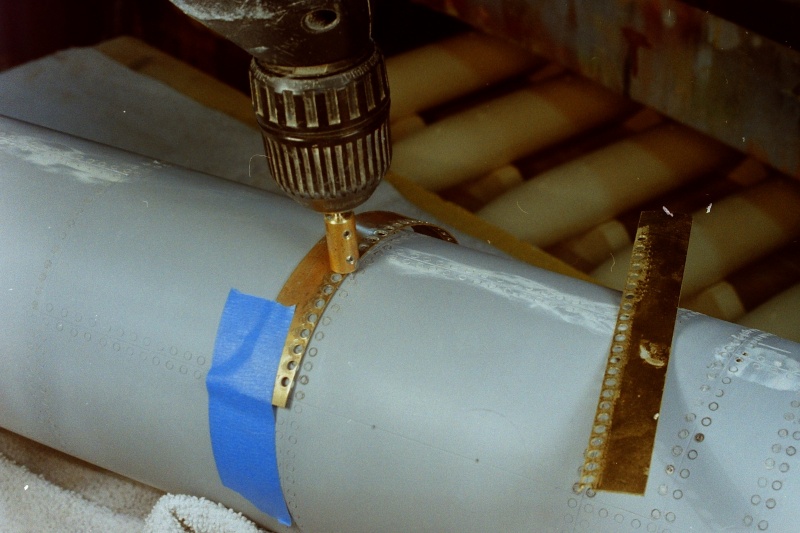

A rotary cutting tool would actually engrave the small circles representing rivet heads. On the mill -- taking advantage of the indexed X-slide hand-wheel, which gave me perfectly uniform spacing -- I drilled guide-holes into annealed brass strips. Those drilled strips becoming indexed drilling jigs used to give uniform spacing and depth as the rotary cutter engraved the little circles into the surface of the hull.

Sandpaper adhered to the face of drilling jigs prevented them from sliding around on the model as the rotary tool was employed. A positional arbor around the cutting bit permitted precise adjustment of cut-depth.

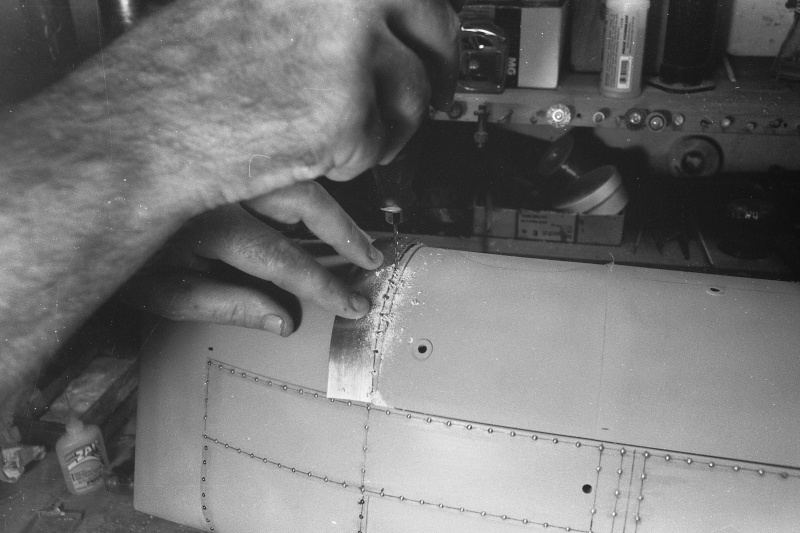

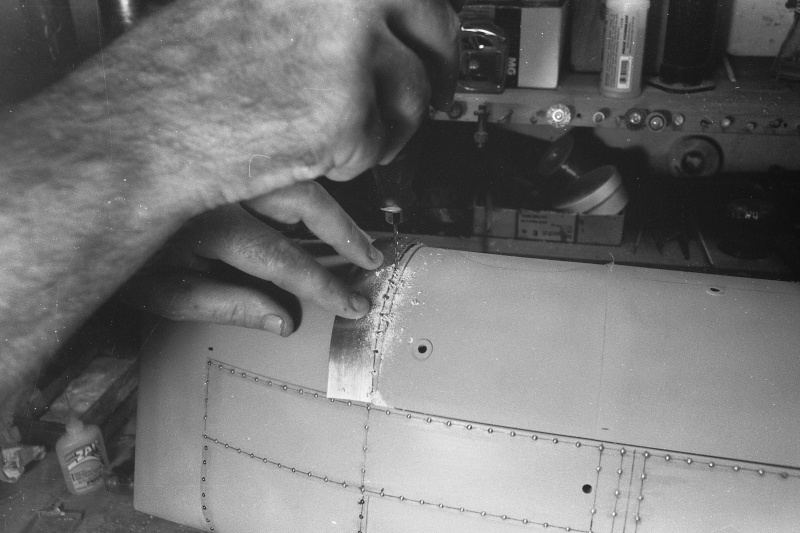

Invariably some of the hulls gel-coat was damaged in and outside the engraved circle. The fix, after completing a row of engraved rivets, was to drive automotive filler into the work. Before it could cure hard, each engraved circle was chased out with a hand controlled scratch-awl.

And here is the desired effect: engraved straight radial and longitudinal lines denoting where one piece of metal plate butted up to another with round engraved circles representing counter-sunk rivet heads sitting flush with the hull plating.

FLAT-HEAD RIVETS AS PUNCHED OUT POLYSTYRENE DISCS I elected to show a difference in rivet types used on the ALLIGATOR. As initially built the actual ALLIGATOR was powered by an array of oars, not the propeller later installed after a significant overhaul. This and the other major alterations/up-grades occurred at a different yard than the one that built the ALLIGATOR. I assumed there would be different construction practices between the two yards, and these would evidence as such on the reconfigured submarine. Hence, flush counter-sunk rivets for the basic hull; and round, high sitting flat-head rivets for the new structures.

The ALLIGATOR sits somewhere, safe and secure from examination, on the continental- shelf off the American East Coast, so I'm very confident that I'm right in my conclusions as to the submarines detailed fittings.

(Move over and make some room W.A. Alexander, it's me, David Merriman)

So, those added on features, such as the blanking plates over the discarded oar stuffing tubes; propeller extension piece; rudder doubler plates, rudder packing castings; and diver and conning hatch combings, all featured flat-head type rivets that stood proud of the structures they held together.

I modified the heel of an anvil by cutting a slit 1/2" below and parallel with its face. I then drilled an array of different sized vertical holes which passed all the way through the anvils heel , close enough to the heel to transverse the slit. This created a handy punch-cutter tool suited to making little discs of plastic or soft metal.

In operation, as you see here, a suitable thickness of material is inserted in the slit and a punch is installed into the appropriate hole and tapped with a hammer to punch out the disc, which drops out of the bottom of the anvils heel. This is how I created all the flat-head rivets needed for the flange and doubler plate items on the ALLIGATOR model.

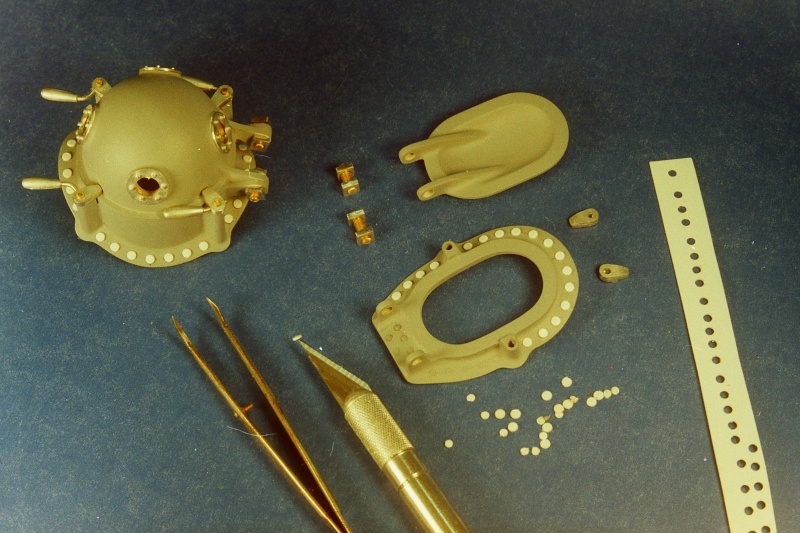

The doubler plates that reinforced the rudder-to-rudder operating shaft union were given the flat-head rivet treatment. Study of contemporary structural use of doubler plates and rivet patterns guided me as I did this sort of work. Incidentally, what I'm doing in this shot is making use of polystyrene square stock to represent machine nuts.

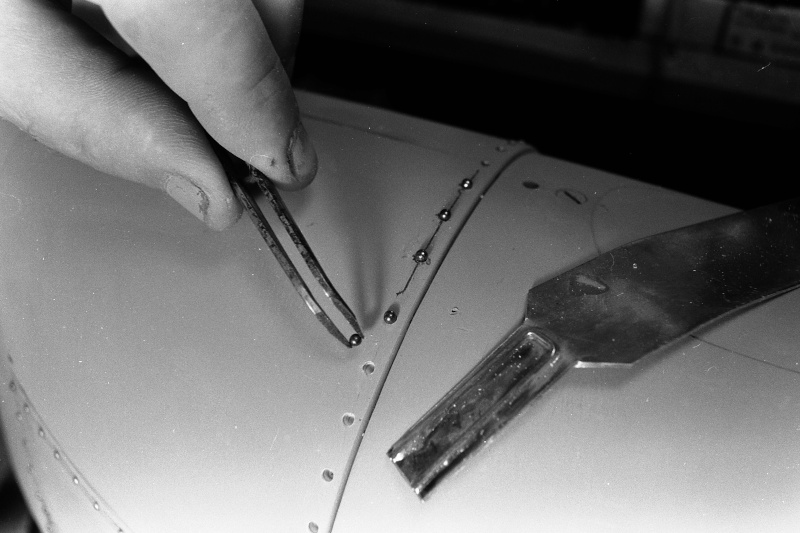

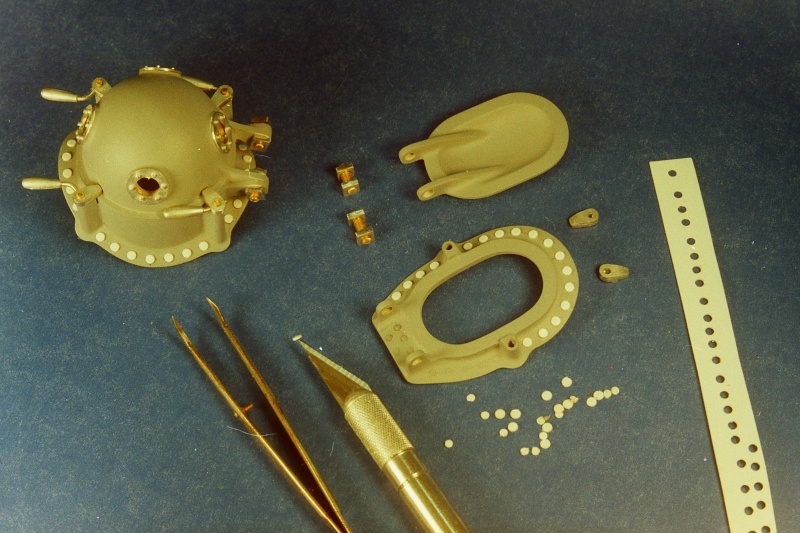

After marking a flange where the flat-had rivet is to go, a rivet is picked up with the point of an X-Acto blade; a very small drop of CA is placed on the rivets underside; and the rivet carefully positioned over the flange and pressed into place.

Not rivets, but in this example little turned nubs with slotted heads to represent screw type fasteners. This shot demonstrates that model rivets ( like real rivets) can be inserted into holes with their heads sticking proud to give the illusion of rivets.

Commercially available round-head nails (brads in some circles) can be found in just about any size -- you'll find one to suit your particular job.

ROUND-HEAD RIVETS REPRESENTED BY GLUE-DROPS Just that simple. Drops of glue are placed on the model and permitted to dry/cure hard. A glob of still wet glue, through surface tension, will assume the most economical shape of containment, in this case a hemisphere -- which is pretty much what an old style round-head rivet looks like. The advantage to this type rivet representation is that the work goes very quickly, and mistakes are easily wiped or scrapped off the surface being worked.

Exothermic curing (two-part) adhesives are best for this work as the mass of the glue droplet is rather large. So, if you used a solvent (be that solvent water or a much more active chemistry) evaporating type adhesive you would find that though it went down nicely, that over time that drop of glue gave up a sizable fraction of its mass to evaporation and turned into an ugly raisin looking thing. Ugh!

That's why exothermic curing adhesives (epoxy is one) are ideal for rivet making -- they retain their mass during the state change from liquid to solid. However, there are situations where, if the size of the glue rivet is small enough, an air-dry adhesives can be used to make your rivets with no negative consequences.

I first was exposed to this type rivet representation through the excellent articles authored by Tom Sherman, as he described how he adorned his scratch-built Disney NAUTILUS models with little drops of glue. And that's the technique I used on this 1/24 HUNLEY static display piece.

As it turned out the actual HUNLEY is a purpose built submarine. Original in both design and construction. So, the this models high relief rivet heads, steering linkage, hull form, torpedo boom, cut-waters, hatches and combings -- all based on the W.A. Alexander drawings -- were at considerable variance to reality.

Oh, well. At least no one's asked for their money back... yet.

I used a very thick, metal filled epoxy for the little drops that represent rivets on this model. The high surface tension of the goo permitted small diameter yet high hemispheres of glue -- the intent was to high-light the fact that the HUNLY was built (we thought) from a converted steam boiler.

SPHERES AS ROUND-HEAD RIVETS If brad nails are not available in the head size required that will scale with the work and the size is larger than what would work using the dab-of-glue technique, there still remains alternative methods of representing the rivets.

This 1/12 HUNLY model made use of steel bird-shot balls. The object of the game here is to drill a hole in the model that presents a moderately tight interference fit between hole and ball, and to press the ball have-way into the hole. The projecting hemisphere representing, perfectly, the hemisphere of a round-head type rivet.

Though a nice looking model of the HUNLEY when running on or under the water, this model is also an extremely poor representation of the actual war craft: The plating is lap attached, not butt joined; the appendages are (at best) approximations; the torpedo spar is in the wrong position; and the rivets are round-head, not counter-sunk with their heads flush to the hull.

Ten years after this model was completed the actual HUNLEY was raised and restoration work began -- and her secrets began to be revealed: the big surprise was that her hull was not a converted boiler, but a purpose built structure.

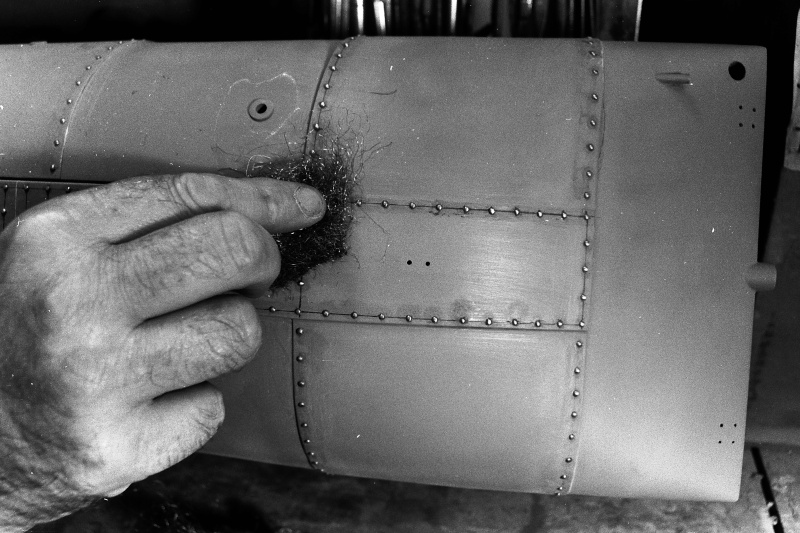

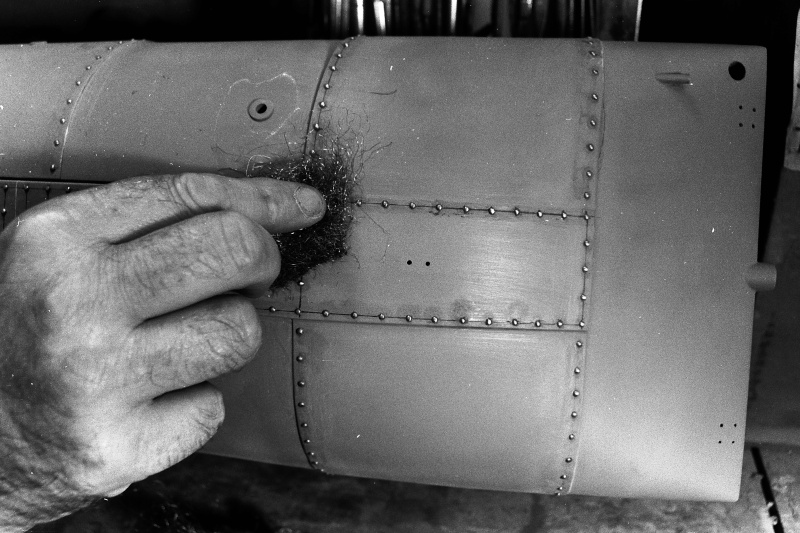

Rivet work can only proceed once the models surface has been brought to a high degree of fidelity -- you don't want to be working around rivets as you address surface pits and projections! So, long before I even thought about the rivet aspect of the job, I worked to get the model completed, with a smooth, unblemished surface. Only then was it time to lay down the rivets.

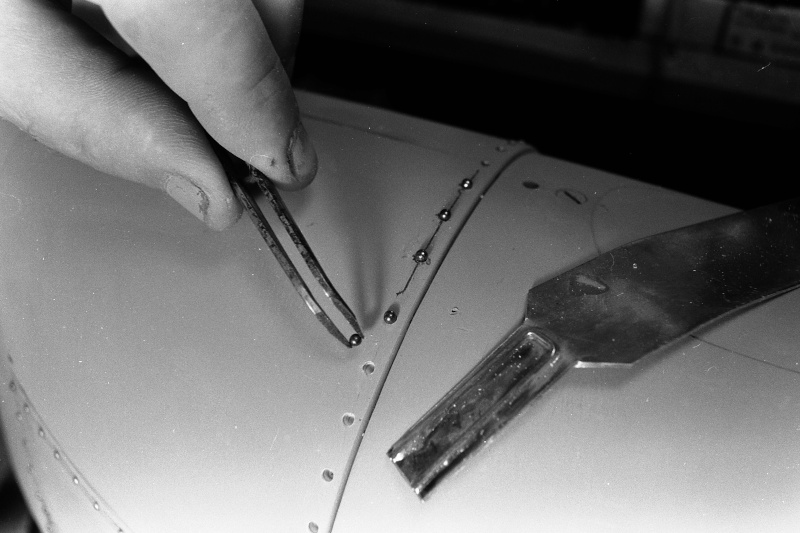

And this is how I did the round-head rivets. From left to right: thin formula CA used to hold the balls in place; the ball spacing gauge and drilling jig; a cordless drill for punching in the holes the balls would fit; the pusher-plate tool used to set the depth each ball sat in within a hole; tweezers for handling the little steel balls; and a box of bird-shot.

The drilling jig assured equal spacing between rivet holes. Made from a piece of brass sheet, this jig was bent to conform to the radius of the hull while drilling the radial rivet runs, and straightened when guiding the drill bit along the longitudinal rivet runs.

A steel ball was placed into a hole and the pusher plate applied over the ball and pressed home, driving the ball only half-way into the hole before stopping -- the two flukes of the tool (which straddle a ball during setting) standing off of the face of the pusher plate a distance that was exactly the same as the radius of the little steel ball.

As a row of steel balls went down, the work was over-coated with thin formula CA and the excess glue quickly wiped off. I then worked over the area with steel wool to clean up the very tight radius fillets between glue and steel ball. From this point primer was applied and sanded back carefully, working around each 'rivet head' ... lots of work!

David

Up to the beginning of the twentieth century the accepted method of joining together ship hull plating was through the use of rivet type mechanical fasteners. In the beginning these rivets had a head and heal that stood proud of the hulls exterior and interior. The flush fitting rivets -- where the V-shaped head of the rivet compressed into the chamfered hole of the plate -- came into vogue, in some applications, during the later nineteenth century.

This discussion will be focused on the three most common rivet types we would see on a ship or submarine built in the, 'age of sail'.

Before the almost universal practice of welding had replaced the rivet as the principle means of affixing metal hull plates together, rivets were the preferred method of bonding metal-to-metal. And, as you would guess, there were many different head styles of rivet, as well as patterns to which the rivets were laid down.

Presented here are model representations of the round, flat, and counter-sunk type rivets. The subjects are a r/c 1/16 USS ALLIGATOR; an r/c 1/12 HUNLEY Confederate privateer; and a smaller static display 1/24 HUNLEY.

Before launching into the discussion proper, I want to inform the reader that both HUNLEY models used as examples here were commissioned and built long before the HUNLEY revelations -- after examination of the salvaged original submarine off the coast of Charleston.

it's interesting to note that the Confederate And Union submarines of the Civil War were both constructed of metal butt-joined (carvel plating) metal plate held tightly together by counter-sunk rivet s whose round heads were flat and flush with the outer surface of the hull. A streamlining measure only recently appreciated my marine vessel Conservators and historians.

(It was not until the salvage and examination of the actual HUNLEY did we realize the error all the illustrators and model-builders made previous to that revelation: we all assumed round-head rivets sticking high and proud off the submarines hull).

The two HUNLEY models are presented here to demonstrate two different technique for representing round-head type rivets over lap-joined and radial clinker hull plating. These models are poor representations of the actual HUNLEY submarine, but have utility here as very good rivet application training-aids.

THE SUBJECTS CHOSEN TO DEMONSTRATE MY RIVETING TECHNIQUES

This 1/16 scale effects miniature represents the USS ALLIGATOR. America's first commissioned submarine. It commissioned for and appeared on the Discovery Science Channel episode, The Hunt For The Alligator. A fully capable r/c model submarine, this effects miniature featured screw-type propeller propulsion; a gas type ballast sub-system; deployable anchor; practical diver and conning hatches; and practical suspension floats -- used to stabilize the boat about the pitch axis and suspend the submarine at specific depth from the surface through deployment and recovery of the float lines.

(An interesting aside: While filming the TV show it was found that the deployed stabilization buoys raised the vehicles center of buoyancy so high above its center of gravity that even at a significant advance through the water, the static stability of the boat about the pitch axis was so high as to counter the dynamic forces that would have otherwise (with a closely coupled c.b. and c.g.) made the boat unstable about the pitch axis. The ALLIGATOR had no horizontal control surfaces! No active means of controlling the boats pitch angle. Yet, it was found during our use of the effects miniatures during production, that with the buoys deployed (as seen in this production shot) that I could control the boat easily by slight changes in the amount of ballast water aboard. The deployed buoys keep the submarine on a near zero pitch angle -- deep control was effected by ballast water taken on/pumped out alone!).

The 1/12 HUNLEY: Though I was not involved in the hull construction of this model, I was dragooned into the project as the initial builders became preoccupied with other work. I took on this model after receiving the basic hull, with little else. Because this model is based on the W.A. Alexander sketches -- a document so highly referenced over the decades as to have become almost canon until recent times -- this model IS NOT a proper representation of what we now know the HUNLEY to be.

If only we had followed the Chapman miniature painting and pencil studies -- which were first-person depictions of the vessel -- we would have been very close to what the Conservators recently found out.

The written and illustrated history bit me on the ass on this one.

However, I did complete the model and r/c'ed it for the customer. And it worked surprisingly well underwater. As long as the speed was kept below a critical limit, the single set of bow planes was enough to effect good depth control. But, above the critical speed the boat would either pitch up or down violently. And that's why the real boat worked so well: being man powered, it could never attain a speed where the static stability of the boat was defeated by hydrodynamic forces created as a consequence of speed, i.e. the boat worked because it was slow. It was man-powered.

This wooden and cast resin 1/24 static display model was commissioned by a collector. And, like the above r/c HUNLEY was built based on the rather inaccurate drawings based on the sketches of W.A. Alexander.

NOW ... THE RIVETS DISCUSSION

COUNTER-SUNK (FLUSH) RIVETS AS ENGRAVED CIRCLES The little known (historian's have been so negligent in regards to this incredible submarine) or appreciated Union ALLIGATOR, a contemporary of the Confederate HUNLEY, likely was built with the same type materials and fasteners as her southern sister. I was commissioned to build model, an effects miniature, representing the arrangement of the ALLAGATOR shortly before its loss while being towed around Cape Hatteras.

A fortunate circumstance: at the time the salvaged HUNLEY was giving up her secrets, I began design and physical work on the miniature -- I endeavored to detail the ALLIGATOR by representing the same type plating joins, fasteners, and manufacturing techniques seen on the HUNLEY.

That meant that the hull plating rivets would be represented as circles, each defining the perimeter of the rivet head as it sat in its chamfered hole in the plate. The models hull would have to be engraved with hundreds of little circles. On the other hand, those structures mounted onto the hull would be outfitted with simulated flat type rivets, that sat proud upon the items mounting flange -- those rivets represented by little punched out discs of .010" polystyrene sheet.

The hull proper, a GRP structure with a heavy gel-coat serving as the outer substrate, was first marked off with pencil to denote the butt plate joins.

The productions main art-director and ALLIGATOR expert, Jim Christly, informed me that the hull was likely made from rolled sheet of iron plate that came from the mill in four-foot wide sections. Scaling that to the model gave me the longitudinal distance between engraved radial lines (used to represent the butt-joints between plates).

Scribing scratch-awl and razor saw were used to cut in the radial and longitudinal engraved lines -- I had planned for this when laying up the hull GRP parts -- having taken care to provide a very heavily filled gel-coat before laying down the glass laminates. It's easy to scribe soft gel-coat. It's a complete son-of-bitch to engrave across strands of glass! A lesson learned early in my model-building career.

A rotary cutting tool would actually engrave the small circles representing rivet heads. On the mill -- taking advantage of the indexed X-slide hand-wheel, which gave me perfectly uniform spacing -- I drilled guide-holes into annealed brass strips. Those drilled strips becoming indexed drilling jigs used to give uniform spacing and depth as the rotary cutter engraved the little circles into the surface of the hull.

Sandpaper adhered to the face of drilling jigs prevented them from sliding around on the model as the rotary tool was employed. A positional arbor around the cutting bit permitted precise adjustment of cut-depth.

Invariably some of the hulls gel-coat was damaged in and outside the engraved circle. The fix, after completing a row of engraved rivets, was to drive automotive filler into the work. Before it could cure hard, each engraved circle was chased out with a hand controlled scratch-awl.

And here is the desired effect: engraved straight radial and longitudinal lines denoting where one piece of metal plate butted up to another with round engraved circles representing counter-sunk rivet heads sitting flush with the hull plating.

FLAT-HEAD RIVETS AS PUNCHED OUT POLYSTYRENE DISCS I elected to show a difference in rivet types used on the ALLIGATOR. As initially built the actual ALLIGATOR was powered by an array of oars, not the propeller later installed after a significant overhaul. This and the other major alterations/up-grades occurred at a different yard than the one that built the ALLIGATOR. I assumed there would be different construction practices between the two yards, and these would evidence as such on the reconfigured submarine. Hence, flush counter-sunk rivets for the basic hull; and round, high sitting flat-head rivets for the new structures.

The ALLIGATOR sits somewhere, safe and secure from examination, on the continental- shelf off the American East Coast, so I'm very confident that I'm right in my conclusions as to the submarines detailed fittings.

(Move over and make some room W.A. Alexander, it's me, David Merriman)

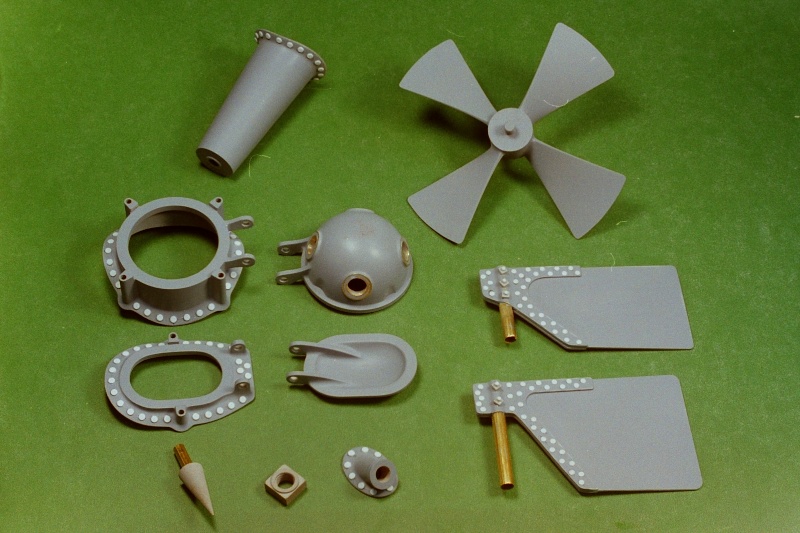

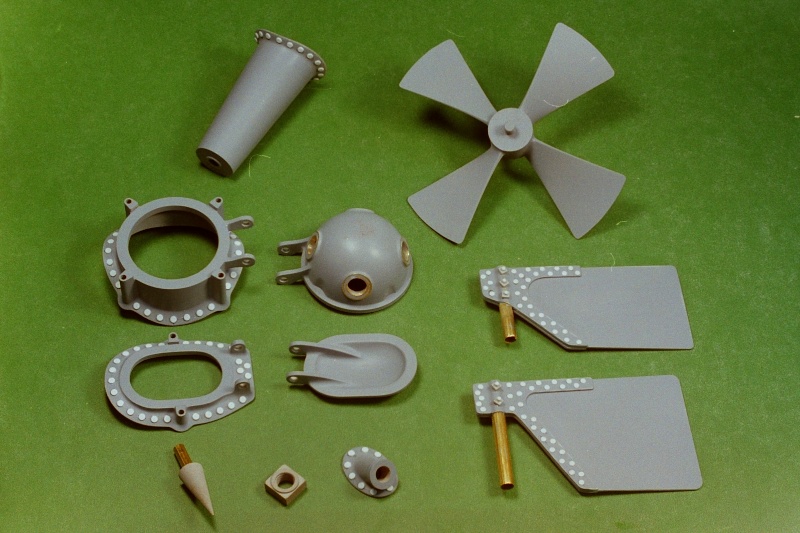

So, those added on features, such as the blanking plates over the discarded oar stuffing tubes; propeller extension piece; rudder doubler plates, rudder packing castings; and diver and conning hatch combings, all featured flat-head type rivets that stood proud of the structures they held together.

I modified the heel of an anvil by cutting a slit 1/2" below and parallel with its face. I then drilled an array of different sized vertical holes which passed all the way through the anvils heel , close enough to the heel to transverse the slit. This created a handy punch-cutter tool suited to making little discs of plastic or soft metal.

In operation, as you see here, a suitable thickness of material is inserted in the slit and a punch is installed into the appropriate hole and tapped with a hammer to punch out the disc, which drops out of the bottom of the anvils heel. This is how I created all the flat-head rivets needed for the flange and doubler plate items on the ALLIGATOR model.

The doubler plates that reinforced the rudder-to-rudder operating shaft union were given the flat-head rivet treatment. Study of contemporary structural use of doubler plates and rivet patterns guided me as I did this sort of work. Incidentally, what I'm doing in this shot is making use of polystyrene square stock to represent machine nuts.

After marking a flange where the flat-had rivet is to go, a rivet is picked up with the point of an X-Acto blade; a very small drop of CA is placed on the rivets underside; and the rivet carefully positioned over the flange and pressed into place.

Not rivets, but in this example little turned nubs with slotted heads to represent screw type fasteners. This shot demonstrates that model rivets ( like real rivets) can be inserted into holes with their heads sticking proud to give the illusion of rivets.

Commercially available round-head nails (brads in some circles) can be found in just about any size -- you'll find one to suit your particular job.

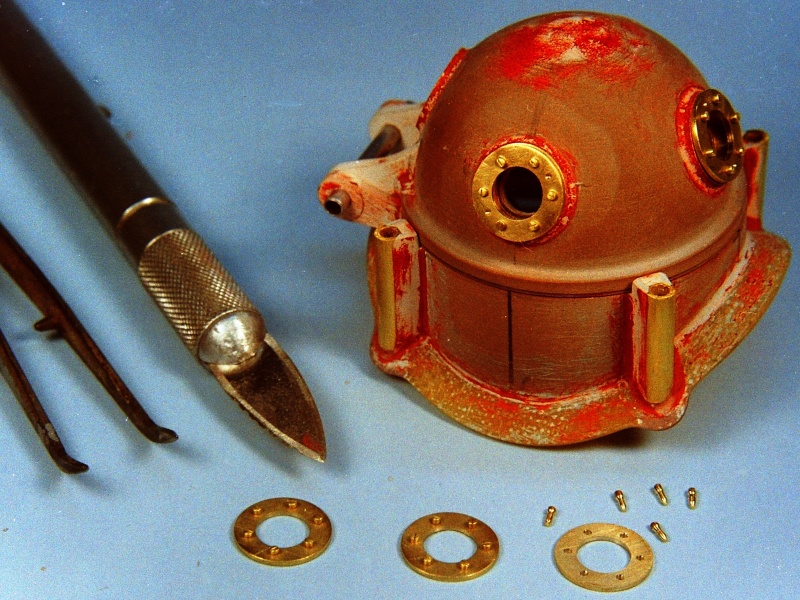

ROUND-HEAD RIVETS REPRESENTED BY GLUE-DROPS Just that simple. Drops of glue are placed on the model and permitted to dry/cure hard. A glob of still wet glue, through surface tension, will assume the most economical shape of containment, in this case a hemisphere -- which is pretty much what an old style round-head rivet looks like. The advantage to this type rivet representation is that the work goes very quickly, and mistakes are easily wiped or scrapped off the surface being worked.

Exothermic curing (two-part) adhesives are best for this work as the mass of the glue droplet is rather large. So, if you used a solvent (be that solvent water or a much more active chemistry) evaporating type adhesive you would find that though it went down nicely, that over time that drop of glue gave up a sizable fraction of its mass to evaporation and turned into an ugly raisin looking thing. Ugh!

That's why exothermic curing adhesives (epoxy is one) are ideal for rivet making -- they retain their mass during the state change from liquid to solid. However, there are situations where, if the size of the glue rivet is small enough, an air-dry adhesives can be used to make your rivets with no negative consequences.

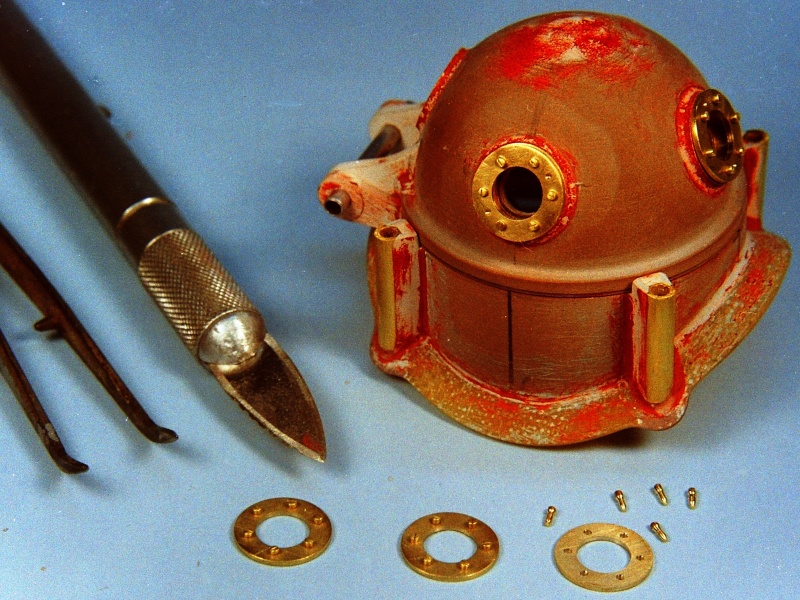

I first was exposed to this type rivet representation through the excellent articles authored by Tom Sherman, as he described how he adorned his scratch-built Disney NAUTILUS models with little drops of glue. And that's the technique I used on this 1/24 HUNLEY static display piece.

As it turned out the actual HUNLEY is a purpose built submarine. Original in both design and construction. So, the this models high relief rivet heads, steering linkage, hull form, torpedo boom, cut-waters, hatches and combings -- all based on the W.A. Alexander drawings -- were at considerable variance to reality.

Oh, well. At least no one's asked for their money back... yet.

I used a very thick, metal filled epoxy for the little drops that represent rivets on this model. The high surface tension of the goo permitted small diameter yet high hemispheres of glue -- the intent was to high-light the fact that the HUNLY was built (we thought) from a converted steam boiler.

SPHERES AS ROUND-HEAD RIVETS If brad nails are not available in the head size required that will scale with the work and the size is larger than what would work using the dab-of-glue technique, there still remains alternative methods of representing the rivets.

This 1/12 HUNLY model made use of steel bird-shot balls. The object of the game here is to drill a hole in the model that presents a moderately tight interference fit between hole and ball, and to press the ball have-way into the hole. The projecting hemisphere representing, perfectly, the hemisphere of a round-head type rivet.

Though a nice looking model of the HUNLEY when running on or under the water, this model is also an extremely poor representation of the actual war craft: The plating is lap attached, not butt joined; the appendages are (at best) approximations; the torpedo spar is in the wrong position; and the rivets are round-head, not counter-sunk with their heads flush to the hull.

Ten years after this model was completed the actual HUNLEY was raised and restoration work began -- and her secrets began to be revealed: the big surprise was that her hull was not a converted boiler, but a purpose built structure.

Rivet work can only proceed once the models surface has been brought to a high degree of fidelity -- you don't want to be working around rivets as you address surface pits and projections! So, long before I even thought about the rivet aspect of the job, I worked to get the model completed, with a smooth, unblemished surface. Only then was it time to lay down the rivets.

And this is how I did the round-head rivets. From left to right: thin formula CA used to hold the balls in place; the ball spacing gauge and drilling jig; a cordless drill for punching in the holes the balls would fit; the pusher-plate tool used to set the depth each ball sat in within a hole; tweezers for handling the little steel balls; and a box of bird-shot.

The drilling jig assured equal spacing between rivet holes. Made from a piece of brass sheet, this jig was bent to conform to the radius of the hull while drilling the radial rivet runs, and straightened when guiding the drill bit along the longitudinal rivet runs.

A steel ball was placed into a hole and the pusher plate applied over the ball and pressed home, driving the ball only half-way into the hole before stopping -- the two flukes of the tool (which straddle a ball during setting) standing off of the face of the pusher plate a distance that was exactly the same as the radius of the little steel ball.

As a row of steel balls went down, the work was over-coated with thin formula CA and the excess glue quickly wiped off. I then worked over the area with steel wool to clean up the very tight radius fillets between glue and steel ball. From this point primer was applied and sanded back carefully, working around each 'rivet head' ... lots of work!

David

» WW2 mini sub build

» sonar data link

» Robbe Seawolf V2

» ExpressLRS - 868/915 Mhz equipment

» Flight controllers as sub levelers

» 868/915 Mhz as a viable frequency for submarines.

» Futaba -868/915mhz equipment

» Microgyro pitch controller corrosion